![]() The rate of technological change is accelerating fast, with a full three quarters of Asia Pacific-based business leaders now describing themselves as disrupted, rather than a disruptor, according to a new report on how businesses and regulators are adapting to tech change in the Asia Pacific region.

The rate of technological change is accelerating fast, with a full three quarters of Asia Pacific-based business leaders now describing themselves as disrupted, rather than a disruptor, according to a new report on how businesses and regulators are adapting to tech change in the Asia Pacific region.

In the research from global law firm Baker McKenzie, The Age of Hypercomplexity: Technology, Business and Regulators in Asia Pacific, this detailed survey of business leaders in the world’s fastest growing region found well-established, often pre-internet launched businesses are struggling to adapt and compete against new entrants born of the online era.

While on balance, companies from no single jurisdiction collectively reported being particularly confident about the challenges posed by the pace of technological change they face, Indian companies are currently the most positive about tech in the region, with a third (31%) of business leaders in India describing their organizations as ‘highly adept’ at exploiting the benefits of new technologies, compared with 14% in Hong Kong, and just 8% in Malaysia.

There was a direct correlation between those companies that described themselves as highly adept at maximizing tech benefits, and those describing their organizations as disruptors, with 25% of Asia Pacific business leaders claiming to be both.

Commenting on the overall findings, Adrian Lawrence, Head of Technology, Media and Telecoms (TMT), Asia Pacific, Baker McKenzie, said:

“Technology-driven disruption is affecting every industry, even those that previously assumed their sector to be immune. While it’s hitting different firms from various directions, and with varying speeds, the consistent message is that disruption is accelerating and timeframes for a considered response are contracting dramatically. Firms that are failing to appreciate that disruption requires a top-down, across the business response are falling behind and risk reaching a point where they will never catch up.”

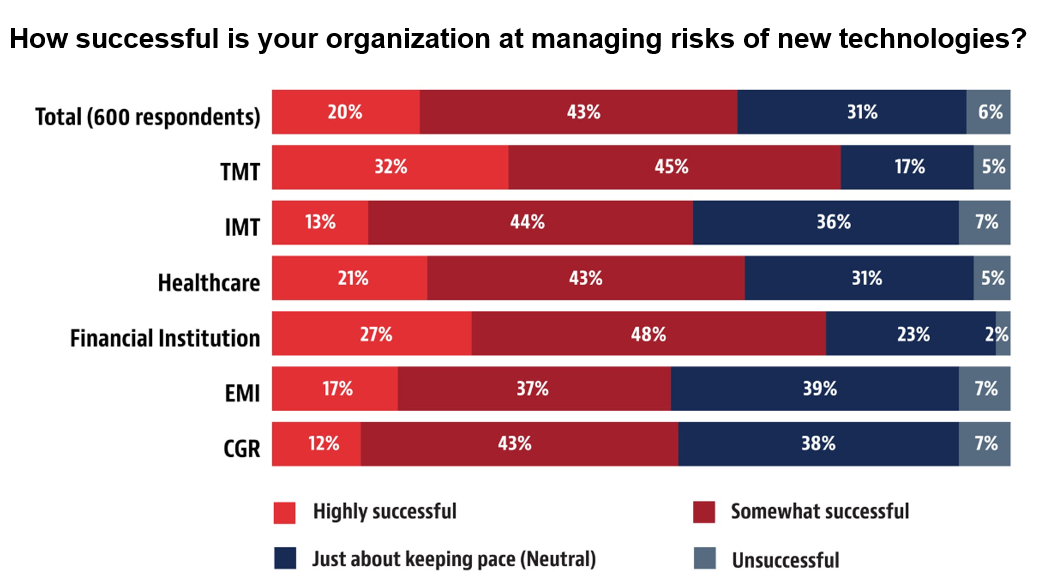

When thinking about the risks associated with technological advancement, just 20% of Asia Pacific business leaders describe themselves as ‘highly successful’ in managing tech risk. Unsurprisingly, the breach or theft of sensitive information was identified as the greatest perceived tech risk.

Of six major sectors* covered by the research, consumer goods & retail (CGR) executives collectively described themselves as the least successful at managing tech risk, despite likely access to a wealth of consumer data.

In their efforts to get ahead of the tech curve, Asia Pacific companies will be focusing primarily on the capture and use of data as the 2020s begin, with 68% of business leaders identifying big data as a key tech focus. This was followed by cloud computing, AI and client relationship management (CRM) systems.

Sonia Baldia, TMT Partner and India specialist, Baker McKenzie, said that as well as being the fuel of the digital economy, getting ahead in terms of data capture, storage, analysis and usage will be a key differentiator in the global economy in the years to come, something India’s tech sector was particularly focused on.

“It is increasingly clear that those who win in terms of data, win in business. The analytics provided around customer behavior, operational efficiencies and cost will provide a clear edge in the decade to come. Leading Indian companies, and multinationals basing their tech operations in India, are alive to this fact, and are preparing for the new data driven age with significant investments in processes and people.”

A more challenging finding for regulators across the region was the assessment by business leaders about how well their own regulators are keeping up with technological change. Just 17% said they were ahead of the curve, 38% said they were somewhat behind the curve, and 46% said they were well behind the curve. On average, Singapore-based executives were most confident in their regulators, although no country had a net-positive score.

Singapore-based Stephanie Magnus, Head of Financial Institutions, Asia Pacific, Baker McKenzie, said:

“The relentless pace of tech change necessarily requires companies to work closely with regulators and policy makers to ensure that companies are heard in the policy-making process and have a sense of where legislation is headed. This can reduce compliance surprises down the road – and that certainty is good for business.”

Tech change is unlikely to slow down in the 2020s. In fact, of the 85% of business leaders that say tech change is accelerating, a third say the rate of change is growing exponentially.

Notes to Editor:

*100 respondents came from each of the six industries, which are: Technology Media, & Telecoms (TMT); Financial Institutions; Consumer Goods & Retail (CG&R); Energy, Mining & Infrastructure (EMI); Healthcare; Industrials, Manufacturing & Transportation (IMT)